Community Land Trusts are a phenomenon taking off fairly recently in Australia and New Zealand, one part of the growing grassroots movement to regain some public control over the availability and prices of housing. Many Community Land Trusts have been well established in North America and the UK for a number of years. These are essentially non-profit corporations accountable to a community-based membership that elects community members and other affected locals onto their board. It is a very exciting idea and provides a model where housing is provided at affordable rates, and also meets other social needs of the local community. The philosophy of the movement is based on communist ideals and has been greatly inspired by Henry George, an American writer, politician and political economist, who’s idea was that poverty stems from elitist land ownership. The drive for the hundreds of CLTs that have already been established in the US has been in order to address the need for low-cost housing. I was lucky enough to be in Melbourne for a workshop on Community Land Trusts by Bob Corker of Kotare Ecovillage in New Zealand.

Bob outlined the key features of CLTs as the following:

- Not-For-Profits – some also looking into charitable status

- Trustees are from the community itself

- Permanent – offers residents security

- Expansionist – can be added to

- No ownership personally – only lease tenure

- Affordability

- Avoids ‘capture’ i.e. by the market in price, or things against the values of the community.

- Restores commons.

I suppose the two most exciting aspects about CLTs for me is the affordability and the onus being on stewardship, not ownership. In modern times we have become very caught up with the idea of owning stuff; land, things, and of autonomy and individualism. The need to have our own property, our own things; to be independent of everyone else, an individual or individual family unit. This has led us into a culture of extreme consumerism and wastefulness, of isolation, loneliness and mental illness. Something is missing from this life! And many people are seeking now, what was once missing. Community, a feeling of belonging. Sharing resources, sharing daily tasks, even meals. And with housing becoming increasingly out of reach of poorer households, first time home-owners, and even of would-be eco-village dwellers, CLTs provide a model which keeps housing at affordable rates, not at fluctuating market rate.

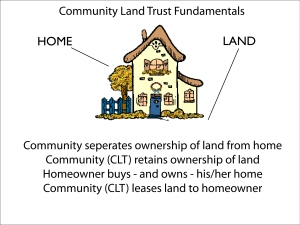

So how does it work? CLTs have been described as a type of “shared equity homeownership” where the rights, responsibilities, risks and rewards of ownership are shared between the households and the organisational stewards. This can be for a new development, say an ‘ecovillage’ or cohousing co-operative setup, and also for a cluster of existing properties. After the initial subsidy is put down, allowing the home to be ‘bought’ for a below-market price, the new owners need to agree to limits to how much the house can be sold for at a later date. This allows the affordability to prevail. The value of the plot may rise slightly according to the CPI index but not the local land market. The residents do not own any one title, but are a lessee of the Trust. The Trust as a whole owns the property collectively. There is even the opportunity to rent inside this model, which is an option for those who cannot afford even to be a lessee in the CLT. Usually new property is built by CLTs, but often existing homes can be brought into the Land Trust. The initial costs for setting up a CLT are high! So many have sought start-up funding from foundations or philanthropists. Sometimes the local government has stepped in to provide some funds and grants for community development.

Bob Corker has set up the Kotare Land Trust after trying pretty much every other model of community or eco-village. The hippy commune, sharing income and work which all fell apart when tense relationships broke down. The business model with individual businesses functioning from common land. The eco-village, which Bob and his wife left when they realised people did not truly share their ideals and huge profits were being made from the on-selling of free-hold titles, even when the original onus was on affordability. They has finally set up a Community Land Trust and this model suits them and their family best.

Bob pointed out that CLTs can be applied to various situations which involve people in rural situations for example farms and eco-communities. The Scottish Isle of Eigg is a famous one, whose residents set up a CLT on the island to buy out their absent feudal landlord and to establish collective governance of their isle. But this can also be extended into urban settings too, as I found out reading an article in YES! Magazine from Summer 2012. The predominantly Latino suburb of Sawmill in Albuqueque in New Mexico, USA, found that soaring house prices were pushing land and housing out of the reach of most families who had lived there for decades. A community action group formed a local CLT and persuaded the local government to purchase 27 acres of vacant land, and eventually the titles to this land was handed over to the CLT. Different CLTs are set up with different missions. Some are groups of residents looking to improve their neighbourhood. Sometimes they are created as a response to market pressure that threatens to displace vulnerable residents. Some are led by Non-profit organisations like Habitat for Humanity in the US. Some are even government projects. But in all cases they are grassroots projects, championed by people passionate about creating affordable housing.

CLTs can have a lesser environmental foot print than your average neighbourhood too, and many enter into them with strong environmental ideals. For example at Kotare Land Trust in New Zealand, there are strict regulations in place regarding the specifications of new buildings; they must be single storey, modest in floor space, and made with as many natural materials as possible i.e. earth, and no toxic substances. They have composting toilets, no septic tank, rocket stoves, and biofuel.

The organisational set-up may seem a little bewildering in the beginning, it did to me! But it is essentially quite simple and can vary from project to project. One way that Bob Corker described is as follows: Initially the group starting the CLT will need to set up a Private Development Corporation if they plan on doing new developments. Once this development of the property is complete, this corporation can then dissolve to form the Community Land Trust, and the board of Trustees is established with members from the community itself (majority) and members of the local area or local businesses. This board is elected and make all the over-arching decisions regarding the running and development of the CLT. These act as the “elders”, offering wisdom from experience and they protect the community with culture, not law. An Incorporated Society Committee, made up of all the residents, acts as the democratic arm of the community, managing common areas, makes certain decisions, deals with maintenance, and is the voice of the people referring back to the Board of Trustees. Bob suggests an educational institute and co-operative businesses can be established within each CLT to provide an income and employment to members. For example, Bob runs his permaculture education and seed saving centre, the Koanga Institute from within Kotare. A diagram of the organisational setup of Kotare can be seen below:

Community Land Trusts offer an exciting alternative model, particularly for marginalised populations who find themselves increasingly pushed out of the housing market. The rates to be a lessee may still be out of reach for some, but then there is the option to still be a part of it, by renting. It is less about banks and borrowing and more about community. It excites me because it brings custodianship and stewardship back into our way of thinking, and control of our housing and resources back to the people!

Have a look at the link below to read about Kotare on the Permaculture Research Institute of Australia’s website:

Sawmill CLT’s website: www.sawmillclt.org/

Rebecca